Epilepsy

Epilepsy is often the first sign of an eventual diagnosis of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, with many people living with both conditions

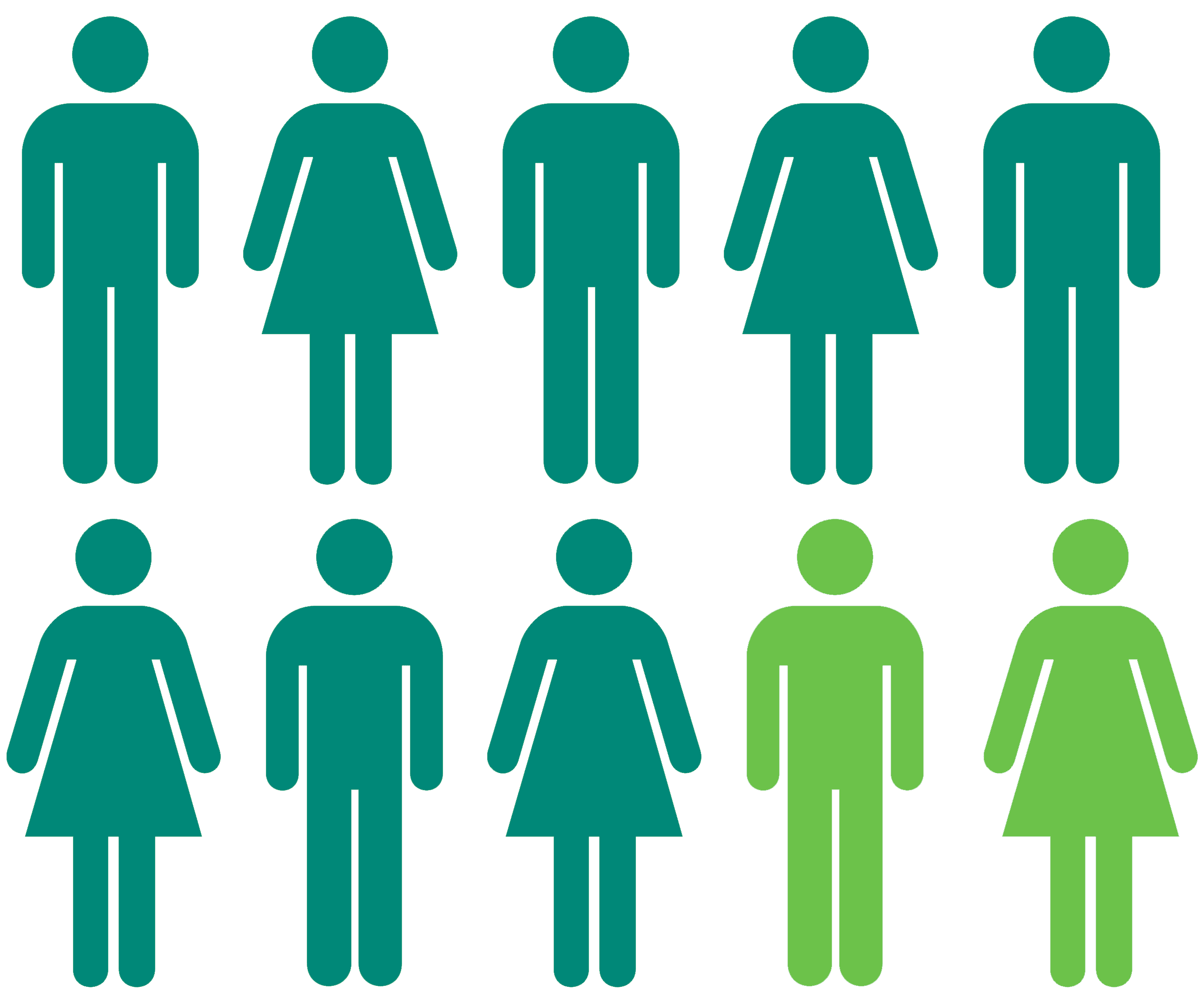

Epilepsy is very common in people living with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), with around eight in every 10 people living with TSC also experiencing epilepsy at some point in their lives.

Although TSC-related epilepsy can be diagnosed at any age, it often begins in the early years or childhood – seven out of every 10 children living with TSC also develop epilepsy.

For many young children the first sign that they may be affected by TSC is epilepsy. Some infants with TSC may have ‘infantile spasms’. Parents who think that their child might be experiencing infantile spasms should seeks medical help as soon as possible (more about infantile spasms here).

It is not always possible to control all seizures that a person with TSC-related epilepsy has. When you, your child or a loved one is diagnosed with TSC-related epilepsy it can also be a very worrying and confusing time.

Although it is a common and potentially confusing or distressing issue, with the right information and support many people living with TSC-related epilepsy can go on to live fulfilling lives with a few changes to their daily routines.

Around eight in every 10 people living with TSC also have epilepsy

What is epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a neurological (brain) condition that means a person is more likely to have epileptic seizures (‘fits’). Epileptic seizures happen because of a sudden increase in electrical activity in the brain, which temporarily disrupts how the brain would normally work.

Messages in the brain get mixed up, which leads to the person having an epileptic seizure.

It is vital that TSC-related epilepsy is promptly diagnosed and treated. Throughout the UK there are specialist epilepsy centres and several epilepsy organisations that have comprehensive advice and support on all aspects of epilepsy. Some NHS TSC clinics have a particular speciality in TSC and epilepsy.

The TSA holds regular virtual and face-to-face meetings about all different areas of TSC. Epilepsy-focused talks included the two shared here, focused on treatments for TSC-related epilepsy and TSC-related epilepsy more broadly:

Epilepsy and TSC

Why is epilepsy common in people with TSC?

Epilepsy is the most common neurological feature in TSC. It is thought that that epilepsy occurs in TSC due to areas of abnormal brain development, called cortical tubers. Cortical tubers are disorganised areas of the brain that contain changes to nerve cells.

There are many different types of epileptic seizures and people with TSC often develop different types as they age. Although most epilepsy in TSC starts in children, it can also begin in adults.

What is the outlook for people living with TSC-related epilepsy?

The outcome for children and adults with TSC-related epilepsy varies enormously. Some children and adults will respond to medication quickly and stop having spasms, although around one in two of these children will begin to have different seizures months or even years later.

Many people living with TSC-related epilepsy continue to live rich and fulfilling lives, despite the condition usually being with them for life in some form.

Steps towards an epilepsy diagnosis

Help your doctor diagnose TSC-related epilepsy

It can be sometimes difficult for epilepsy to be diagnosed quickly, as seizures might develop at different rates or happen at different times.

People living with TSC, their family members and carers can often play an important role in helping to diagnose TSC-related epilepsy. Being vigilant of the signs and symptoms of epilepsy, recording seizures and keeping a seizure diary can all be vital in getting an epilespy diagnosis.

How is TSC-related epilepsy diagnosed?

There is no one test for epilepsy and it may take time and several seizures before a diagnosis is achieved, which can be a frustrating and distressing experience.

Typically, someone suspected of TSC-related epilepsy will undergo an EEG (Electroencephalogram), which records electrical activity in the brain.

Further tests include a CT scan (computerised tomography) or MRI scan (magnetic resonance imaging). For most people living with TSC, these scans will show tubers which could help diagnose epilepsy.

What are some of the different seizures that a person living with TSC might have?

Focal seizures are the most common seizure in people living with TSC. These seizures may cause a sudden strange mix of feelings, emotions and thoughts. The person remains fully conscious and may still talk or interact with surroundings. This may be accompanied by jerking of one side of the face, arm or leg. The seizure may also accompany a slight dreaminess or lack of awareness. A ‘complex’ partial seizure may last for a few seconds to many minutes.

Around four out of every 10 infants under the age of two who live with TSC will develop a type of epilepsy called ‘infantile spasms’. A child with infantile spasms will jerk suddenly in all or some parts of the body. Infantile spasms are often and easily mistaken for other conditions, such as the ‘startle reflex’ in newborns, colic or reflux.

If left untreated, infantile spasms may result in the developmental delay of the child. For this reason, it is important that parents or carers who think that a child might be experiencing infantile spasms seeks medical advice as soon as possible.

Infantile spasms may first appear subtle, such as a gentle head nod or chin thrust. These movements are usually brief and occur several times in a row. Over time, the signs of seizures tend to become more pronounced jerking movements. Most commonly, infantile spasms happen either first thing in the morning or on waking from a nap. The child will often seem sleepy afterwards, despite having only just woken up.

Once a child begins to have infantile spasms, you may notice that their development slows down. There could be a loss of skills that the child had previously learned, with the child possibly becoming less interested in people and their surroundings. The child’s sleep pattern may become disrupted and they may seem irritable, distant or just different from their usual self.

Infantile spasms can be different from child to child, but as a parent or carer you are the best person to notice changes in your child. Therefore, it is important that your concerns are taken seriously by a clinician should you raise them.

With thanks to the European TSC Association, we are also pleased to share the below videos discussing infantile spasms in detail, the importance of early intervention and treatment options.

Previously known as ‘petit mal’ attacks, absence seizures usually occur frequently but briefly (lasting 5-30 seconds) and are rare in people living with TSC. Someone experiencing an absence seizure may briefly loose awareness, stop talking or appear to stare into the distance. There are no abnormal movements in an absence seizure.

Atonic Seizures are sometimes called ‘drop attacks’ or ‘astatic seizures’. Someone experiencing an atonic seizure will suddenly fall to the ground without warning. However, they quickly become conscious and alert again. There is a high risk of injury to the head and face, with some people wearing protective head gear. Children who have other seizure types may also have atonic seizures.

Myoclonic seizures are quite common in children with TSC. Myoclonic seizures look like a sudden shock or startle and can involve the whole body, one side of the body, the face or just one arm or leg. Seizures often happen just after waking or when tired, before going to bed.

Tonic-clonic seizures used to be described as a ‘grand mal’ attack. They are the type of seizure that most people think of when they hear the word ‘epilepsy’. Tonic-clonic seizures begins with a tonic (stiffening) phase, followed by a clonic (jerking) phase. The seizures usually last 2-3 minutes.

What are some of the ways to treat or manage TSC-related epilepsy?

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs, also called anticonvulsants) will not cure epilepsy but aim to prevent or reduce the number of future seizures. Many people with epilepsy will be prescribed an AED, but the types of epilepsy that occur in people with TSC can be difficult to control, with some AEDs working better than others for some people. Unfortunately, more than one in two people with TSC-related epilepsy will not respond to standard AEDs and may need an alternative form of treatment.

Treatments for TSC-related epilepsy include everolimus (brand name Votubia, available across all UK nations), and cannabidiol (brand name Epidyolex, recently approved for use in Wales and Scotland – more information here and here). We’re continuing to work with decision-makers in England in the push to get access to cannabidiol in England – but, the earliest we can hope for access in England is March 2023 at best (with Northern Ireland typically following decisions by England).

Finding the right medication and dosage to treat TSC-related epilepsy with an AED can take time, as it could involve trying several different drugs before the most effective one with the least side effects is identified for an individual. Sometimes, a combination of two AEDs is needed to achieve the best results.

The ketogenic diet involves the consumption of foods which have high fat, low carbohydrates and moderate protein. Ketogenic diets have been found to be potentially helpful for some people whose TSC-related epilepsy is difficult to control through medicine alone.

There are several variations of this diet, but all are based on the principle of using a strictly controlled diet to enable the body to produce ketones, a chemical that is thought to possibly reduce seizures.

The ketogenic diet is not effective for everyone and may result in a reduction or improvement in seizures. The diet requires commitment from the family and close supervision from a trained dietitian.

For a very small number of children and adults whose TSC-related epilepsy does not respond to antiepileptic medication, surgery could be an effective treatment option. There are a range of different surgical operations that might be suitable, depending on the circumstances of every individual.

One of the most common surgical option in epilepsy is called ‘resective surgery’, which involves removing an area of the brain which has abnormal nerve cells. Resective surgery is rarely performed in children with TSC-related epilepsy, as children with the condition often have more than one area of abnormal nerve cells in their brain.

Another option includes vagal nerve stimulation (VNS). VNS involves implanting a watch-sized electrical stimulator under the skin below the left collar-bone, with very thin wires (called electrodes) then leading to the vagus nerve, located in the neck. The electrical signal stimulates the nerve at regular intervals, which has been found to reduce the frequency and intensity of epileptic seizures.

Epilepsy surgery must be performed at designated epilepsy surgery centres in the UK, such as Children’s Epilepsy Surgery Service (CESS) centres.

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

If you live with TSC, you might also be diagnosed with other conditions that are related to the condition, depending on how TSC affects you. Some children and adults who live with TSC and severe epilepsy are also diagnosed with a condition called Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS) is a severe form of childhood epilepsy, but it can start as late as teenage years. People with LGS may experience multiple types of seizures, learning difficulties and/or challenging behaviours.

If your child has severe epilepsy with multiple types of seizures, you may wish to speak to your child’s hospital specialist (usually a paediatric or adult neurologist) to see if a secondary diagnosis of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome can be made. In order to reach a diagnosis of LGS, your clinicians may need to arrange an EEG electroencephalogram test.

LGS can be difficult to treat with anti-epileptic medicines, with most children and adults with LGS requiring a combination of medicines and other therapies. Recently, Epidyolex (cannabidiol) was approved and recommended by NHS England to treat seizures associated with LGS for adults and children aged two years and older – this includes those in the TSC community who have LGS.

If your child has a secondary diagnosis of LGS, you may wish to talk to their hospital specialist about whether cannabidiol could be a suitable treatment option to help manage their epilepsy (if your child is not already prescribed cannabidiol).

More information on cannabidiol’s approval’s for LGS can be found on the NICE website here.

Some people living with TSC also have something called epilepsy. A person living with TSC can get epilepsy at any age, but it usually starts when someone is a child.

If a person’s epilepsy is because they also have TSC, it is called ‘TSC-related epilepsy’. Not everyone who lives with TSC will get epilepsy.

Epilepsy can affect people very differently. But a person with epilepsy can still have a happy life.

What is epilepsy?

Epilepsy causes something called ‘seizures’, which are sometimes called ‘fits’. Epilepsy happens when messages in the brain get mixed up.

What might someone having a seizure do?

There are different types of seizures that have different effects.

Sometimes a person’s body might start moving suddenly or go very stiff when they are having a seiure. Someone who is having a seizure might fall to the ground or be unable to control their movements for a little while. Someone having a seizure might still be able to talk, or might feel or act differently to normal.

How do I find out if I have TSC-related epilepsy?

There is no single test for epilepsy. It can take time and different tests to find out if someone has it. It is normal to feel frustrated or anxious because of this.

When doctors are trying to find out if someone has TSC-related epilepsy, they might ask the person to write down all the times that they have had seizures. This is called a ‘seizure diary’.

How can someone with TSC-related epilepsy feel better?

There are different medicines for people with TSC-related epilepsy. Some might work, some might not. Sometimes a person might need surgery or try eating different foods. Epilepsy is different for everyone.

Download resources

Useful links

Related pages

Make a one off or regular donation

£10 Can allow us to send a welcome pack to a family who has just received a life-changing TSC diagnosis, ensuring that they do not go through this time alone.

£25 Can help us develop materials that are included in our support services, flagship events or campaigns.

£50 Can provide laboratory equipment for a day’s research into the causes, symptoms, management or treatment of TSC.

To provide help for today and a cure for tomorrow