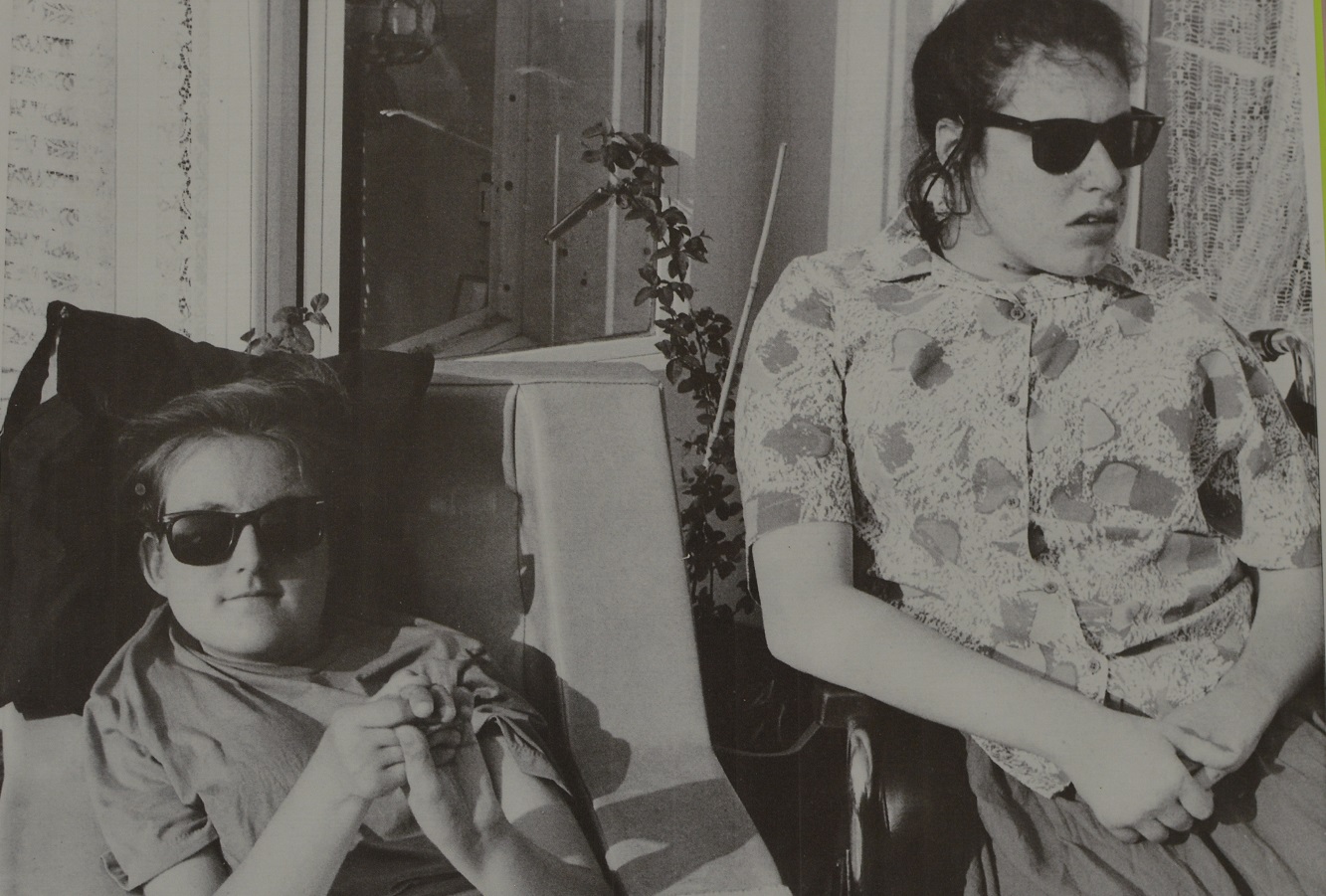

In 1970, Victoria Willson (pictured right) was born in North London. A beautiful baby her parents Jean and Norman were besotted with her. They were

already no strangers to heartache as their elder daughter Tara had been born in 1966 with spina bifida and Jean had suffered three subsequent miscarriages

before Victoria finally came along to complete their family.

But their joy was short lived. Victoria was constantly in hospital with infantile spasms and failing to thrive.

Further hospital stays followed in quick succession – as Jean, a founder member and Trustee of the TSA, puts it: ‘I rapidly became on first

name terms with the bed manager at University College Hospital’ – and then came the moment when the Willson family’s world changed utterly. Whilst

being in hospital with pneumonia, ‘A consultant looked Victoria over with a Woods Light,’ remembers Jean. ‘Then they did yet more tests. And that

was when they told me Victoria had calcified tumours in her brain, she had tuberous sclerosis complex.’

Jean says she was told that there was no hope whatsoever and ‘to put Victoria in a home and forget about her.’

Being given a ‘no hope’ diagnosis by the medical profession was the worst aspect of Victoria’s illness, says Jean.

Jean, however, was not about to take such a prognosis lying down.

‘Those were my handbag throwing days,’ she says, ‘and I stormed out of that office! Alright, a bit later on when I’d calmed down I thought I’d better

go back and listen to them. But that is the absolute worst thing anyone can do to anyone else - to take their hope away.

‘These days the TSA exists to give people hope and purpose when you are floundering around in a minefield of despair.

‘But back then I nearly smacked the geneticist who told me very clinically that Victoria’s TS was a ‘new mutation’ in our family. It sounded like something

out of Star Trek! My first daughter, Tara, was born with spina bifida, and I then had three miscarriages. I was told that Victoria having TSC was

a one in 500 million chance. Looking back, and hearing what some people tell me today, I do think that we need to think about how the medical professional

talks to people with TS and their families, especially at diagnosis, because I know from personal experience that this can be a very, very lonely

and frightening time.’

In the late 1960s and early 1970s days there was nowhere to go for Jean to find out more information, no-one else she knew was affected by TSC, no

support network, and no internet with all the information and contacts that it offers.

So Jean, chronically sleep deprived, exhausted, uncertain but never more determined, found a Parents In Touch magazine and started writing to a mum

in Scotland who had a daughter, Catriona, with TSC.

‘Just that one letter – getting that one letter every week or so from Esther meant so much to me, and to her,’ says Jean. ‘It’s that hope thing. And

it all started from there!’

Now Jean and Esther’s letters have since blossomed into the organisation we now know as the Tuberous Sclerosis Association.

‘I do a sense of satisfaction when I look back to what started off as two mums writing to each other and then think about what the organisation is

now,’ says Jean. ‘There have been some terrific breakthroughs both in terms of campaigning, and treatment – amazing. And we’ve now got a professional

team of people working for us, and we’re not relying on volunteers doing their bit – we have come an awful long way. But we’ve not lost sight of

our grassroots because we’ve got a lot of people on our Board of Trustees who are family carers – we are still very much a family-oriented organisation.’

Jean readily admits that she would ‘change it all in a heartbeat if it would mean that Victoria did not have TS and could live a normal life’. But

then, Jean reflects, that ‘in a really strange, bizarre way, being Victoria’s mum has made me a better person. It made me dig deep and develop

skills that I never knew I could have, and o have powerful tenacity and determination. Victoria was such an inspiration to me, and she absolutely

gave me the motivation to change things.’

Jean pays tribute to the often superhuman efforts made by people caring for their loved ones with TS.

‘I didn’t sleep for Victoria’s first five years, because she didn’t sleep. She just screamed. And it was a bold social worker who said to me ‘How long

do you think you can keep this up?’ In those days I was a very angry mum, and until I had Victoria I didn’t even know what a social worker was!

‘But somehow, I managed to listen to him and Victoria went into respite so at least we could have a break. Then she went into a residential home 130

miles away from her home because that was the only place in the whole of England that would take her.

‘It nearly broke me. She was there from the age of five years old to eight, and to this day I remember all the pain and anguish of it all. So I know

what so many people are going through.

‘But as family carers we have to look after our own health too. So many times I’ve put off going to the doctor and the dentist for myself, I’ve even

put off having an operation, because of caring for Victoria.

‘I’ve seen too many family carers of people with TS lose a partner, and then lose their child as well, and then what? And don’t forget siblings. Unless

you talk about it, it will always be there, burbling away in the background – who is going to look after your offspring with TS when you die.

We made it very clear from the start that Tara was is no way responsible for her sister Victoria, unless, of course she wanted to be.’

‘So’, concludes Jean, ‘the biggest gift you can give your child – any child, but especially a child with TS – is independence. If you work towards

that now, step by step, day by day, then that’s your insurance policy. Right from the word go people need to think about making sure their child

can live independently, in whatever form that takes, because once you’ve got that worked out, it’s one less thing to worry about and you can get

on with the business of living.’